(b. 1975, lives and work in Detroit)

By Laura Mott, Curator of Contemporary Art and Design, Cranbrook Art Museum

The coyotes roaming Detroit fascinate artist Scott Hocking, it is an animal that is adaptable and gregarious, yet also solitary and rejects human domestication. Hocking encounters them on his sojourns through the parts of the city where post-industrial urban landscape is in the process of being reclaimed by nature. He creates photographs, sculpture, and assemblages in these places of transition; likewise, he is a coyote-like roamer in pursuit of evidence and archeological specimens created by the modern human species. The coyote is a frequent character in the folklore of the Western World going back to Mesoamerican cosmology—a picaresque figure that has the ability to assume both human and animal form. It is easy to conjure such a fantastical character around Hocking, because he is more of a scavenger than flâneur, and his work is more mythology than documentary.

The pairing of man versus nature is a trope used throughout the history of literature and film; and the metaphor is often used as a device to grapple with existential constructs like the sublime. When I began to think about interviewing Scott Hocking, defining elements of his practice—his artistic character, the landscape, the mythologies, the dramatic visuals—resonated as having a distinctive cinematic quality with the overtures of grand storytelling. In addition, the work he creates is never static in the present, even if it is a printed photograph. There is a suggested narrative of a before and an after, whether that be a remnant of an event or the anticipation of one. Therefore, in preparation of the following interview, I asked him to watch three movies that had elements relatable or tangential to his process, aesthetics, and work: The Night of the Hunter (1955), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and The Five Obstructions (2003). In brief summation, The Night of the Hunter is a black and white noir film directed by Charles Laughton, and stars Robert Mitchum as a fanatical preacher/ serial killer that chases two children for weeks along a rural landscape. Close Encounters of the Third Kind is a science fiction film by Steven Spielberg in which the protagonist’s hysteria is beset upon him due to an encounter with a UFO, resulting in him leaving earth with the aliens. The Five Obstructions is a documentary by Lars Van Trier in which he challenges his mentor, Danish filmmaker Juergen Leth, to remake his film The Perfect Human (1967) five times under increasingly difficult creative restrictions and challenges.

After both of us watched these films, we met to discuss. This interview took place on July 4, 2016, in Scott Hocking’s studio during a particularly hot summer in Detroit.

—————

Scott Hocking: My first reaction to the list of films was it is fantastic you selected The Night of the Hunter; it’s one of my all time favorites.

Laura Mott: I think it is essential viewing for artists and filmmakers. The Night of the Hunter is a film in which the narrative is greatly amplified through the director’s use of space and light. I thought we could begin our discussion surrounding the drama of night, because I know it is an important time for your process and explorations of Detroit. My dominant memory of The Night of The Hunter was Robert Mitchum’s silhouette slowly moving across the stark, empty landscape of night: an image that spoke to the equivalency often made between desolation and danger. The lighting of the film in particular made me think about your photographs. I thought you might want to talk about the night as a resource.

SH: When I photograph at night, it’s an extension of me being a kid. Like those kids in [The Night of the Hunter] who escape in the middle of the night, I would sneak out in the night. Some of my early memories when I was living in Redford [Michigan] were walking down the railroad tracks at night. Even to this day the railroad tracks are this hidden pathway that crisscrosses the country, the globe really. When you walk the railroad tracks you are removed from the rest of life. You see nature in a different way, you see things hidden in the background.

It occurred to me I needed to document these experiences, the same way it occurred to me to document the ways I work in abandoned buildings. Making artwork with the materials I find from these places, doesn’t translate the feeling of being there, the photographs have become a little bit closer. Sometimes I’m alone for hours in a desolate section of the city, places I don’t think many people see. I enjoy the time I spend just getting one shot, the quietude.

Davison Fog Mound, from Detroit Nights, 2007-2016

SH: (continued): I realized the projects I’m doing in Detroit, whether it be a photo series of Detroit at night, aging signs or graffiti, or making installations in places long ruined or desolated, I realized there is a time limit. I won’t be able to do them any longer, the city is changing—even the night photos. For a long time the night photography had a lot to do with the randomness of the street lights, the ambient light situations of Detroit were so unpredictable and you’d find an area that was incredibly desolate, but it would have one working lamp lighting nothing. Or there would be neighborhoods that would be bustling but all the streetlights would be broken. But that has all changed. The city has experienced a huge amount of infrastructure improvements, where all the public lighting has been upgraded to LEDs. They are on every street, even the abandoned ones.

LM: There is another aspect of The Night of the Hunter I wanted to discuss—the fanaticism. The killer’s fanatic beliefs are a driving force for much of the story. This tradition of storytelling can be the impetus and the drive for so many real life actions, good and evil. In your own work you take up such topics, like your project The End of The World (2012), which is a stacked collection of over 200 books about the apocalypse and destruction mythologies. And also there is your recent epic installation, The Celestial Ship of the North (2015), in which you painstakingly inverted an old barn into an ark. I have this idea that you find productive creative value in the fanatic heart and mind.

The End of the World, 2012

SH: [Robert Mitchum’s character] could woo the fanatical masses. The people believed he was channeling the word of God. Something he said reminded me of a book I picked up years ago that lead to the theme you are mentioning called Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.

LM: Wow, good title.

SH: What a great title right? The book was about events throughout history that led to mass hysteria. The End of The World project is about how many times throughout history humans have thought they could figure out how the world would end, and the different forms of these predictions from mythology, to religion, to spirituality, to scientific or pseudoscientific ideas of the sun burning out or a comet hitting the earth. All of these things are examples of humans trying to understand what the hell we are doing on earth and whether this is real or not. The meaning of life, where do we come from, where do we go, what happened before our life, what happens after we die—all of these fundamental questions and attempts at answers.

Right now, logic, reason and scientific methods lead us to believe certain things about where we come from, where we are going; but, I still feel like even that is guessing. I am fascinated by the way humans try to understand what cannot be understood, with stories, with equations. And I am fascinated by archetypes, the way people respond to imagery that has existed forever and that we all interpret in our own way, through our own filters. So if I make something that resembles an ark, that word resonates with people for different reasons. People would come up to me while I was building the ark and shout up to me things like, “Oh you’re like Noah up there,” but they were also kind of testing to see what my response would be. Other people had the reaction, “Jesus, Scott sure is really doing a lot of biblical themed artworks lately, what’s going on there?”

Celestial Ship of the North (Emergency Ark), aka the Barnboat, 2015

Celestial Ship of the North (Emergency Ark), aka the Barnboat, 2015

LM: My thinking is the way your photographs capture the feeling of being in those desolate places, the large-scale installations convey the overwhelming task of tackling human existence. The excess of material, the scale, and the space—the decisions you make as an artist respects the size of the question. Your ark, like Noah’s ark, is something to behold.

SH: In Detroit, the amount of information in the massive, old industrial buildings is incredibly overwhelming – the layers of paint, the layers of history, the layers of material, and the way nature had infiltrated – has made it even more complex. All of your senses are awake. All of your senses become aware because of the unknown. The ark is effective in the sense that driving around the areas in rural Midwestern America, it’s not unusual to come across farms or barns, but the ark makes you do a double take. If you go into an abandoned building and you find a pyramid or an egg built out of material found in there, your reaction might be, “Who did that? Where did they come from?” The what-the-fuck-moment for me is important, but it also comes from my internal desire to find those in my life, to feel like I’ve discovered something unknown.

LM: In Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the main character builds a sculptural landscape in his living room because of subliminal communication with aliens, and it struck me as conceivable—since you work in abandoned spaces—that you would create something like that in a place that might previously been someone’s living room.

SH: Close Encounters, I did kind of think to myself, “Oh she’s sending me this because she thinks I’m that crazy guy!” (laughs) I do sometimes get ideas through dreams. If I have a moment of clarity and it leads to an idea, even if I don’t understand why, I’ve learned to trust it. Projects in Detroit like The Egg in Michigan Central Train Station, the Ziggurat in Fisher Body 21, and the Garden of the Gods in the Packard Plant – in every case I had a feeling I had to do something now. And in every case I could not have done those projects afterwards, the circumstances changed, the buildings were altered, the materials gone.

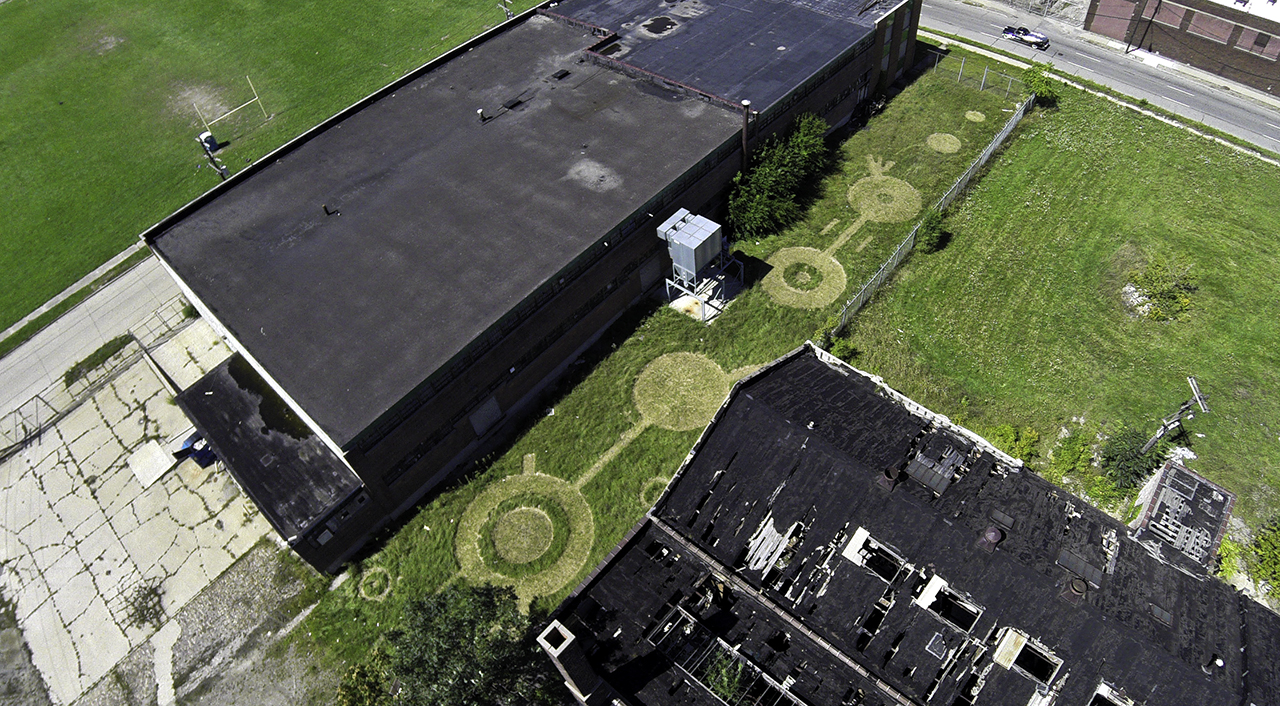

LM: There are certain sculptural elements to your work that nod to an innate human desire for symmetry and the ideal object—the egg, the pyramid, the ark, the crop circle—that have a long history drawing back to ancient forms of communication.

SH: I think when I build a ruin within a ruin, or a monument within a monument or a ruin within a monument, what I’m interested in is trying to point out that the ancient idea of a monument or a ruin is no different from the contemporary. Why do we think that these things from the ancient past symbolize the people, but when we look at our contemporary ruins, we can’t think how it will be perceived in the future? Why do we separate ourselves? How are we any different? I don’t think we are; I think there are cycles. We speak different languages, we have different tools, we have different knowledge, but I think the cycles that humans go through are the same all living things go through. It’s a repetitive circumstance, and to that point I think we repeat the same mistakes as older civilizations. Humanity has a very short-term memory.

Lot Circles, 2014

LM: The idea of how future archeologists will see us is a fascinating aspect of your work. However, to take us back to the present, there are also people from our current moment in time who unexpectedly encounter your works left in public or abandoned spaces. It is a very different discovery for someone who does not encounter them within the art context.

SH: My favorite stories involve people who have nothing to do with the art world, especially the people who are regarded as criminals, like scrappers. My best scrapper story involves the pyramid built in the Fisher Body. The pyramid was built with these wood blocks, which have no scrap value, in fact, they are soaked with creosote, which is a carcinogen, and eventually the EPA cleaned out the whole building—destroying the pyramid. While I was working there was a whole crew of scrappers who had gas-powered saws. They were professionals. They would drive their trucks into the building, hide them, go up onto the different floors, climb up ladders, and saw down these giant, metal galvanized pipes. So they are in the building cutting them down, and suddenly it goes silent. I asked one of the scrappers, “What is happening, why did you guys all stop working?” They are on their walkie talkies, and he said, “The city of Detroit is currently outside re-fencing the building.” I Iook outside and there is a 16-foot fence being rolled up around the building. I said, “I’m going to get out of here,” but they said they were cool and going to stay. So I snuck out the side door, went home. The next day I came back and the fence was gone. The scrappers waited for the city to fence off the whole building, waited for the city to leave, and then they took the fence too.

So I come in one day and all of the pipes are gone, including the pipes that ran right over the top of the pyramid. These pipes were probably 8 inches in diameter, maybe 10 feet long, maybe 300 pounds each. The pyramid was untouched. So these guys, who didn’t give a shit about what they were destroying in these buildings, decided to somehow cut down the pipes over my pyramid without it touching it. I had made enough of a connection with them. I don’t even know how they did it. These are the moments that really make it interesting for me.

Ziggurat, East, Summer II, from Ziggurat and Fisher Body 21, 2007-2009

LM: I selected The Five Obstructions, because it speaks so well to the process of artistic creation. My impression is that Lars von Trier makes the film as a way to get his mentor Juergen Leth out of his depression by essentially challenging his friend to get behind the camera and go to different parts of the world. It captures how artists work through the struggle of creative production and find moments that are spectacular.

SH: So, I’m going to go back first to Juergen Leth’s original film “The Perfect Human”. When you watch the whole thing, some of the important parts are these mundane routines and patterns that the human does, including joy and despair. He is with this woman, in a fetal position in bed—instead of sex, he is crying and she’s consoling him. It shows them eating together, but then it shows him alone, eating and murmuring, “Why is joy always so fleeting?” Eventually, he says, “Why did she leave me?” and he repeats this cycle of moving into despair, only to wrap it up by saying, “This is really a good meal.” Then it ends with the beginning of a new cycle.

In my projects, I move through cycles. I move through periods of confidence and moments of doubt. I’ve realized that it’s all about understanding and navigating obstacles—that’s all it is—you are always navigating. I’m no masochist, I’m not Lars von Trier, but I do decide to build ridiculously labor intensive, time-consuming sculptures in abandoned buildings that might take a year. The barn project was so labor intensive that I got tendonitis in both arms. Then eventually I lost feeling in both arms. I couldn’t sleep. I had to sleep sitting up in a chair. But, I know it’s a cycle, I know I’ll get through it. The end object is not the most important thing; it is the process and the meditation of working.

LM: I’m interested in your own process when you venture to new cities and situations, like how did you approach a city like Indianapolis for the exhibition at the Tube Factory? What specific histories, materials, or discoveries of the city led to the creation of this installation?

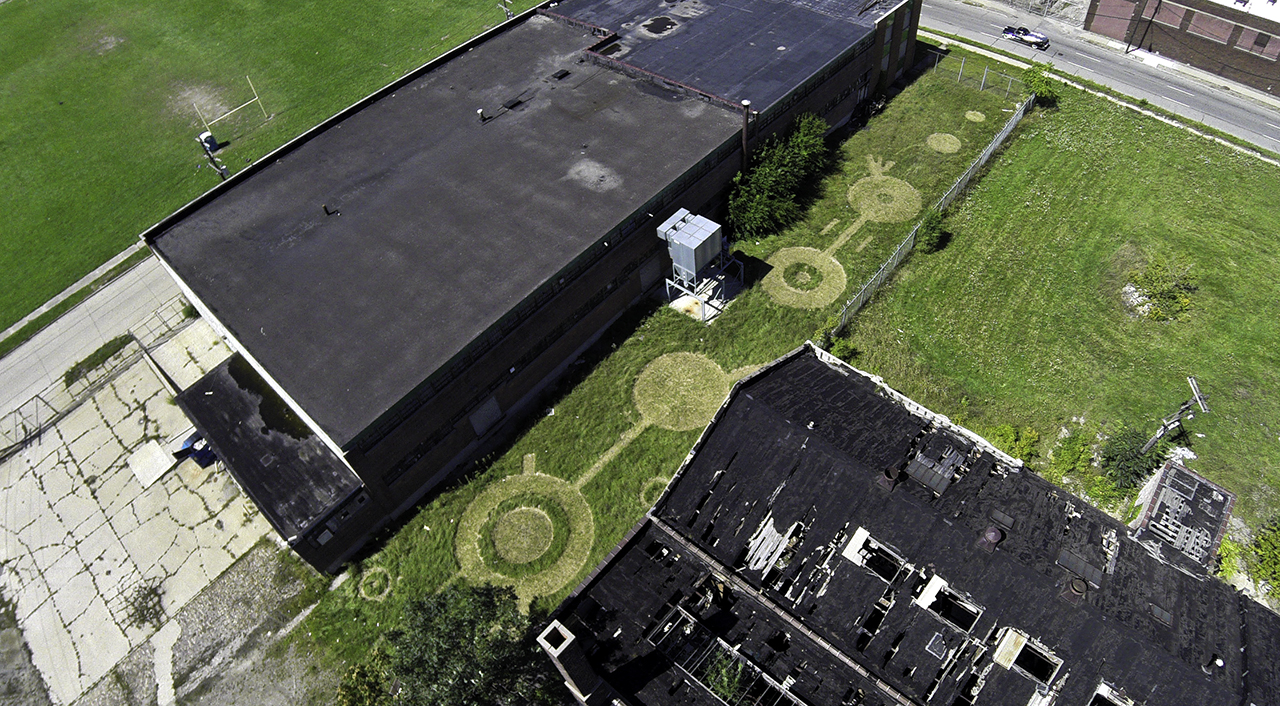

SH: I came out to Indianapolis a couple of times to scout and talk about ideas. The last visit was in January, and Shauta Marsh (the curator at The Tube Factory) had lined up a few specific sites, with the help of Kipp Normand, an artist and walking encyclopedia of Indianapolis history. Kipp spent his childhood in Detroit, and we have a similar interest in old junk. They showed me a massive former RCA plant first, and it immediately grabbed me.

I began researching the RCA building’s history. I learned that the buildings I was working in (the only ones left standing) were the oldest parts of the plant, and the division where record albums were pressed. Apparently, a lot of Elvis records were pressed there, and they could often be heard playing throughout the factory. Another interesting story was that of the “anechoic room”: A sound proof room that was lined floor to ceiling with wedges of foam that kind of pyramid-ed out from the walls / ceiling / floor. There was a floating audio system in the center, suspended by wires, and a floating platform that one would walk out on to perform audio tests. The whole scene felt very sci-fi, and led me to believe that the giant Styrofoam wedges onsite were the right materials to use. In general, from the surroundings of the RCA plant and other industrials neighborhoods, to the Tube Factory compound complete with Bean Creek (a virtual wild kingdom of Indiana wildlife), my explorations of Indianapolis have all fed into the installation.

The RCA history was interesting enough, but the building was last used as a recycling plant, and was filled with now abandoned, un-recycled waste: plastic, paper, foam—thousands of objects. There were huge piles of military grade plastic cases, with ominous stencils: “laser firing simulator system,” “interrogation kit,” “casualty evacuation kit,” “tank weapon gunnery simulation system”. There were pallets of clothes and books (including dozens of old hymnals); plastic pill and dish soap bottles; giant fragments of signage from McDonald’s, Steel City, Family Dollar, Wendy’s; and a monster stack of Styrofoam slabs and wedges, melted and distorted from some failed arson attempts. Once I arrived for installation, I spent about a week documenting and gathering materials onsite, and then another week installing at the Tube Factory.

I was even able to salvage portions of the RCA / Victor logo, painted on an old sheetrock wall, one of the few objects connected to the building’s original history. The resulting installation used the main gallery as a kind of future ceremonial site. I kept thinking about that burnt Styrofoam mountain as some kind of dystopian temple or future glacier, the melted areas almost look and feel like glass. I have been reading a lot of Ballard, and we had talked about Huxley, and the Zamyatin‘s precursor to them all, “WE,” and I think it all combined in my head and melded into another mythological future archaeology (like usual). “WE” specifically talks about the glass wall that separates nature from the humans – and they just see the green color through the glass, the Green Wall. The RCA building had this exact scenario: green plastic skylights illuminating all of the manmade heaps of plastic, foam, and military waste – all kind of tranquilly stagnant -potentially sitting there forever.

Former RCA plant, Indianapolis, 2016

Former RCA plant, Indianapolis, 2016

LM: When I asked Shauta why she was interested in bringing you to Indianapolis, she brought up that your work makes us realize we are surrounded by ephemera, which can be an inconvenient idea to most people. And your photography practice, she likened it to Roland Barthes’ notion that photography is a way to resurrect a person or a place from the dead. I thought this could be an interesting place to end and to ask you to think about the longevity and timeline of your works, particularly those with unpredictable futures.

SH: Someone just asked me about photography the other day, because in a lecture I talked about the ephemeral, the fleeting quality of the sculptures built on site—everything gets destroyed by man or by nature eventually—and the only thing that really lives on are the images. And, I related my belief that it’s more important to embrace the process than it is to embrace the end result, the object. The barn boat, which is technically a permanent project, was built out of a barn which was decaying, and it’s just reformatted in a different shape but it’s still decaying, it’s still subject to the same elements and it will disappear.

This topic comes up a lot in the work where I create situations where I’m playing with obscure objects of worship. I’m curious how future people will perceive us. Will they revere the things we leave behind? Will they see us as the horrible savages of the past who did the dumbest things? It’s kind of comical to think they might revere and find the things we leave behind as talismanic, especially if there are things that would lead to our own destruction. Our trash, all the things we create now that don’t get destroyed over thousands of years, plastics, things like that, I’m really curious to know how those things will be perceived, what they will be used for.

LM: The world might be very similar to the way it is now, lots of faults, lots of cycles, and good ideas and bad ideas.

SH: That’s the thing, it all comes back to this idea that the way I’m thinking now is not exceptional; this is the way people were thinking 500 years ago, this is the way people were thinking 1000 years ago. They were looking around and saying, “The world is gonna end if we don’t stop doing what we are doing.”

This is not new thinking, you know the phrase—the more things change, the more things stay the same. But there is a French way to say that, and it’s a lot cooler.

—————————–

Scott Hocking has exhibited internationally, including the Detroit Institute of Arts, Cranbrook Art Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, the University of Michigan, the Smart Museum of Art, the School of the Art Institute Chicago, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts Museum, the Mattress Factory Art Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, the Kunst-Werke Institute, the Van Abbemuseum, and Kunsthalle Wien. He was recently awarded a Kresge Artist Fellowship, and is represented by Susanne Hilberry Gallery.

Laura Mott joined Cranbrook Art Museum as the Curator of Contemporary Art and Design in November 2013 following an active career as a curator, writer, and lecturer in both the United States and Europe. Previously, she has held various curatorial positions at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, Gothenburg Konsthall, IASPIS in Stockholm, Mission 17 in San Francisco, and The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, where she worked on the 2002 Biennial exhibition and publication. She received her MA in Curatorial Studies at Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, and BFA and BA in Fine Arts and Art History from the University of Texas. Mott was a faculty lecturer at the Valand Academy of Art at University of Gothenburg from 2009-2013.

Made possible by a grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

Celestial Ship of the North (Emergency Ark), aka the Barnboat, 2015

Celestial Ship of the North (Emergency Ark), aka the Barnboat, 2015

Former RCA plant, Indianapolis, 2016

Former RCA plant, Indianapolis, 2016

May 6th sees the release of Will, the revelatory third full-length album by Brooklyn experimental artist

May 6th sees the release of Will, the revelatory third full-length album by Brooklyn experimental artist