Since 2016, Tube Factory artspace — a project of the 20-year-old nonprofit Big Car Collaborative — has served as a contemporary art mainstay that shares top-quality commissioned exhibitions while reimagining the role of cultural institutions in the community.

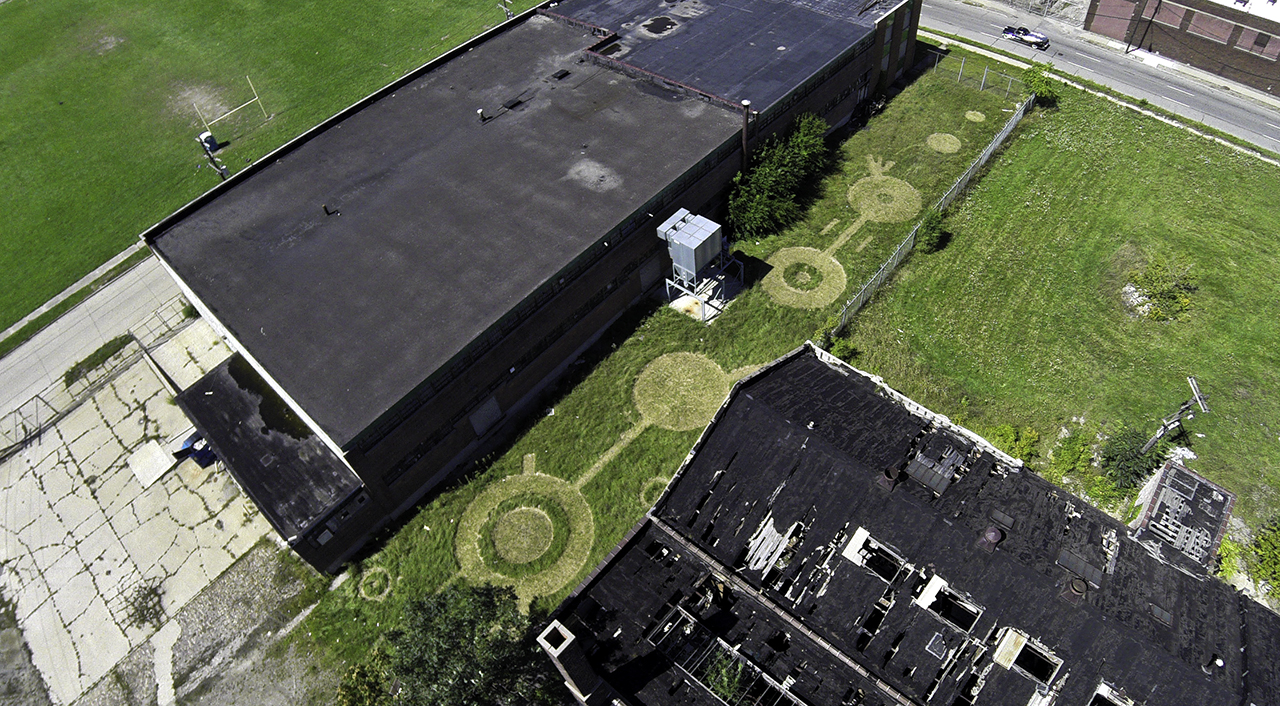

Tube Factory is quadrupling its footprint by adding 40,000 square feet for art in a 125-year-old former dairy barn and industrial space adjacent to its current location just south of Downtown Indianapolis.

While work is now underway thanks to a bridge loan, we at Big Car still have about $1.5 million to raise. People can donate in a variety of ways, with info and online options found here.

In this building expected to open in 2025, visitors will experience five exhibition spaces for contemporary art — including an expansive main gallery for large-scale, immersive installations, 18 studios for artists, a large commercial kitchen offering culinary training and serving the on-site restaurant and bar, five business incubator storefronts, two audio recording studios (including the new home for Big Car’s 99.1 WQRT FM), and a large performing arts and event space.

The sprawling historic building — already stabilized thanks to $1.8 million from a Lilly Endowment Inc. grant Big Car received in 2019 — will anchor the Tube Factory campus that includes a new sculpture park and 18 affordable homes for artists who give back to support the community through their work.

Filling a contemporary art need

With this $8 million expansion, Big Car is making a focused investment in multi-disciplinary contemporary art by going all in to expand its 20-building Tube Factory campus as its city’s contemporary art museum.

“We see now as the perfect time for us to further build a place that reimagines the role of the museum in the community while welcoming visitors from across the street and around the world,” said Big Car co-founder and director of programs and exhibitions, Shauta Marsh. “Pittsburgh has Mattress Factory. Bentonville has The Momentary. Detroit has MOCAD. Cleveland has SPACES. Indianapolis has Tube Factory.”

An important aspect that sets Tube Factory apart from other art spaces in Indianapolis is its approach to curated and commissioned art exhibitions. Tube Factory pays artists directly for producing their shows in the space (and has since its opening in 2016). This approach does not rely on gallery sales for compensating artists.

While the expansion of the Tube Factory builds a place for everyone Marsh said the additional building is also specifically planned to further support artists — with a strong emphasis on supporting artists of color. “This is a continuation of our long-term investment in artists and in strengthening our city overall,” Marsh continued. “Art is a great way to bring people together and help us see new perspectives. Artists are able to address topics and issues that aren’t always easy to talk about.”

In many cities around the world — including Indianapolis — artists have worked hard to boost their neighborhoods and invest time and energy into studio buildings, only to be priced out once they’ve made the spaces more desirable. “That won’t happen here,” said Jim Walker, Big Car’s co-founder and executive director. “Ours is a long-term place, one of very few in our city where the arts nonprofit owns the real estate — ensuring the long-term sustainability of our artist-led campus as a civic commons for culture, creativity, and community.”

Making a long-term investment in art and artists

Many foundations and individuals have generously supported this contemporary art expansion. Major donors to this capital project so far include Lilly Endowment Inc., Allen Whitehill Clowes Charitable Foundation, Efroymson Family Fund, Herbert Simon Family Foundation, The Indianapolis Foundation, Seybert Family Foundation, and Tube Processing Corporation. The project is also supported with financing through the City of Indianapolis’ New Markets Tax Credits program, managed by Indy CDE.

“We believe that these funds-and the amazing things that Big Car Collaborative will do with them-will help us in our aim to establish Indianapolis as a true center for the arts. A center that will not only bring more artists and art appreciators to our city, but also greatly benefit our existing communities,” Indianapolis Mayor Joe Hogsett said at the building’s groundbreaking event on June 18.

“This project is hugely important for our city for a number of reasons. Chief among them is the fact that the Tube Factory fills a significant gap in the art landscape of Indianapolis. It provides a space dedicated to contemporary art and its creators, who make up a crucial part of any thriving art scene,” Hogsett continued.

“These artists also play a huge role in our communities. Through their art, they provide our residents with new avenues of understanding new ways of looking at the world around them. The art serves to bring us together and to help us understand one another. And this is paramount in today’s day and age, when we are simultaneously the most connected and the most divided we have ever been.”

Big Car utilized a bridge loan through IMPACT Central Indiana — a multi-member LLC created by Central Indiana Community Foundation (CICF), The Indianapolis Foundation, and Hamilton County Community Foundation — to get the next phase of construction rolling as Big Car continues to fundraise another $2 million. This fundraising is for repaying the bridge loan and starting a maintenance endowment.

“We’re so very grateful and appreciative of the incredible, transformative support we’ve received so far,” said Big Car board president Jenifer Brown. “Our board and campaign committee have stepped up to help guide us through what’s really our first fundraising effort for a major capital project.”

Indianapolis-based Jungclaus-Campbell is the general contractor on the renovations. Blackline Studio architects worked with Big Car staff on the design.

Another key aspect of Big Car’s Tube Factory expansion is that supporters can see their investment as benefiting Indianapolis artists for many years to come. The Tube Factory buildings aren’t part of another development that could someday change focus.

“It’s very important that our nonprofit organization owns our buildings and that our galleries are dedicated to exhibitions,” said Marsh. “If we were filling a space for a real-estate developer or located in a privately-owned building, our long-term future would always be out of our control. And we might be asked to compromise on how we use the space or censor the content of our exhibits. That won’t happen here. This is a lasting investment in art and artists. It’s not about real estate or making money.”

Space for expanded exhibitions, programs

Backed by an array of local and national funders, Tube Factory has been commissioning work by artists from Indianapolis and around the world since it opened in 2016. Tube Factory’s commissioned artists receive Marsh’s support as a curator in addition to being paid to make new work that might not be possible to sell. Big Car will invest $10,000 to $50,000 in its exhibits that stay up for multiple months.

With a changing landscape for contemporary art that includes the Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art (iMOCA) dissolving as an organization in 2020, Big Car and its supporters see a need to focus even more on bringing innovative and engaging work by today’s artists to a place visitors can enjoy.

As the former executive director and curator at iMOCA, Marsh brought contemporary art museum experience from the very beginning at Tube Factory. As they formed plans and launched programs on the Tube Factory campus, Marsh and Walker visited and researched contemporary art spaces all over the world — many of them adaptive reuse projects.

The result is that a large portion of the bigger Tube Factory building will be dedicated to sharing even more of the kind of contemporary art exhibitions rarely seen in Indianapolis. Like Tube Factory now — which is open for visitors five days a week, including Saturdays and Sundays — this will all happen in a dedicated contemporary art building with regular museum hours for visits.

For example, in 2024, Tube Factory will share a major exhibition by Tulsa-based indigenous-American artist Elisa Harkins. Funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, the Andy Warhol Foundation, Ruth Arts, and the Institute of Museum and Library Services, this commissioned show will fill multiple galleries in Tube Factory for six months. Harkins, who recently received a $100,000 Creative Capital grant for a connected project, has been working with Marsh on this for six years.

The expansion will allow Tube Factory to offer more exhibitions like the one by Harkins — and keep them on display for longer. Like many contemporary art museums around the world, Tube Factory commissions exhibits but does not typically collect work.

Additionally, the new space will offer a flexible, black box space for performing arts groups to put on shows, as well as for special events and mini conferences. The culinary center will provide an opportunity for a unique nonprofit restaurant and bar that will function as an ongoing community-focused art project.

“Artists aren’t always painters or musicians. Chefs, cooks, bakers, bartenders, and baristas are some of the most important and most loved artists in our lives every day,” Walker said. “Food brings people together like nothing else. It’s vital for sharing and celebrating our cultures and our creativity in delicious ways we enjoy.”

History of Big Car and the Tube Factory campus

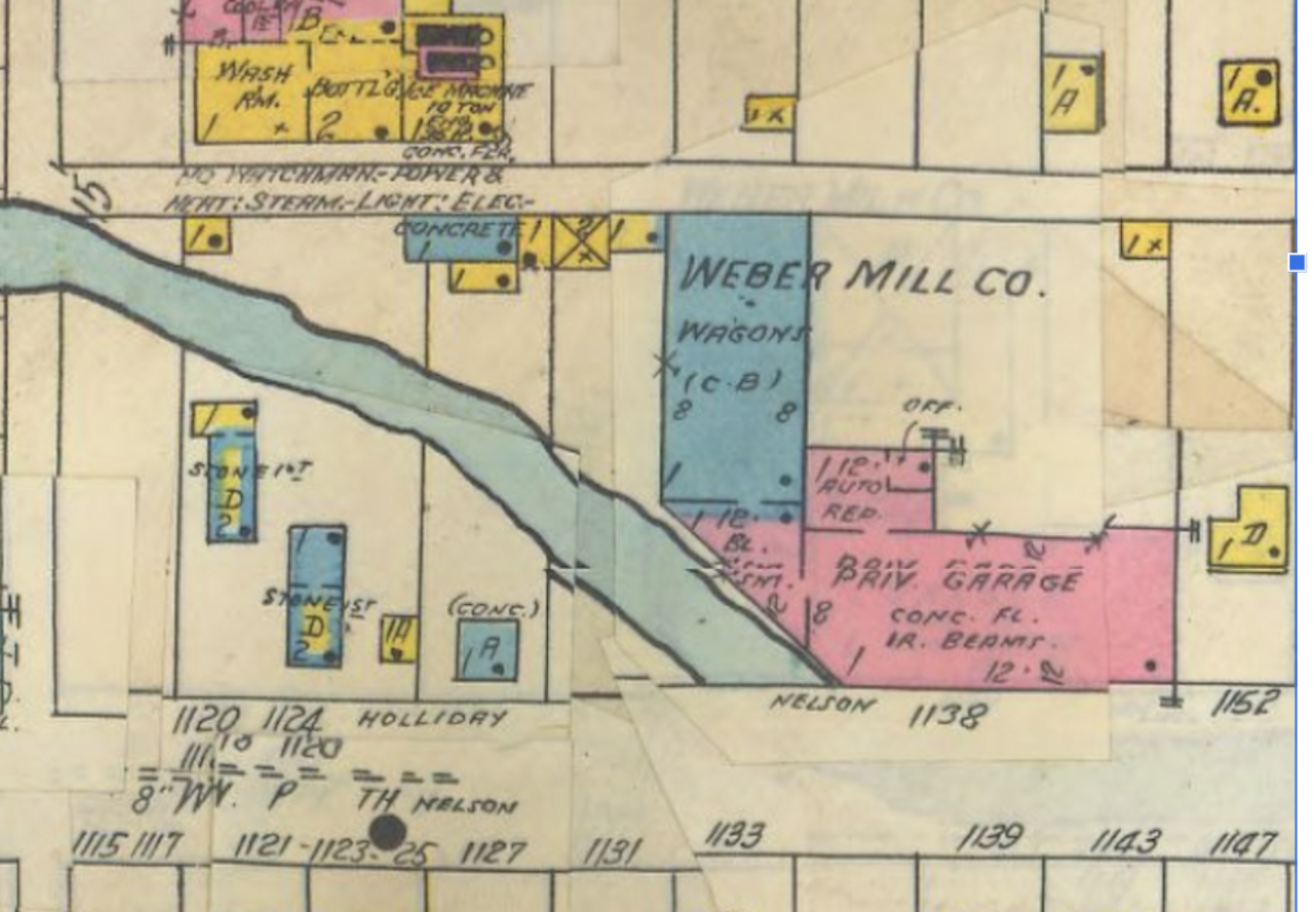

Added to in phases, the building under renovation started small in the late 1800s as a culinary space of sorts — a barn for Weber Dairy. It wound up part of a complex of properties owned by Tube Processing Corporation, a company still located in the neighborhood. Tube Processing donated the building to Big Car in 2021.

Big Car’s current community art center, Tube Factory, was originally a dairy bottling plant and, later, another of the buildings in the complex — also donated by Tube Processing to Big Car in 2015. Tube Factory is now a place where community organizations meet and people gather for cultural programs.

“As a family and company with deep ties to the Garfield Park community and as longtime supporters of the arts, we’re thrilled to support Big Car’s important work at the Tube Factory campus,” said Katie Jacobson, President of Tube Processing and co-chair, with Ken Honeywell, of Big Car’s capital campaign committee. “And we’re glad the Nelson building — with so much history — is being preserved and adapted to be a one-of-a-kind place for art, artists, small business owners, and visitors from the neighborhood and beyond.”

In addition to hosting museum exhibits from artists based in Indianapolis and around the world, the current Tube Factory serves as home base with wood, print, and ceramics shop space for Big Car staff and resident artists in its housing program. Tube Factory is open five days a week with a coffee shop and events like artisan markets that encourage visits by people who might ordinarily participate in the arts.

In addition to fixing up formerly vacant houses on the block since 2015, Big Car also joined three large backyards adjacent to Tube Factory and the big building being renovated now to create Terri Sisson Park: A Shrine for Motherhood. This restorative place — also made possible with the support of Allen Whitehill Clowes Charitable Foundation, Efroymson Family Fund, and others — includes living artworks related to nature including Sam Van Aken’s Tree of 40 Fruit and Juan William Chavez’s Indianapolis Bee Sanctuary.

The park, designed by Daniel Liggett of Rundell Ernstberger Associates, also includes an amphitheater for performances and The Chicken Chapel of Love, a sacred art project led by Marsh to honor the divine feminine and belief systems that center around nature.

Led by Walker and Marsh, who have lived in the Garfield Park neighborhood for 14 years, Big Car has made a deep investment in the near southside since starting work there in 2011. This work includes co-leading a major quality-of-life planning process and offering Tube Factory for gatherings like Garfield Park and Bean Creek neighborhood meetings. Tube Factory is located within both official boundaries.

Throughout its 20-year history, Big Car was often a mobile organization — temporarily filling vacant spaces. The organization learned the importance of owning spaces from taking on projects in buildings Big Car didn’t control — a former tire shop outside then half-empty Lafayette Square Mall and a popular art gallery and music venue in Fountain Square — only to later have to leave those spaces.

A group of artists and neighbors started Big Car in Fountain Square on the near southside of Indianapolis in 2004 as an all-volunteer organization. Still artist run, Big Car now employs 12 people and has operated with an annual budget of about $1 million for the last several years.

By the numbers

- $13 million in planned investment for expansion

- $7.3 million invested so far on the Tube Factory block

- Year Big Car started working on the near southside: 2004

- Year Big Car began its focus on Garfield Park: 2011

- Year Big Car started working on the Tube Factory block: 2015

- Acres owned: 6

- Number of affordable artist homes on the Tube Factory block: 18

- Artists and family members in the affordable homes: 25

Celestial Ship of the North (Emergency Ark), aka the Barnboat, 2015

Celestial Ship of the North (Emergency Ark), aka the Barnboat, 2015

Former RCA plant, Indianapolis, 2016

Former RCA plant, Indianapolis, 2016