by Jim Walker, Big Car Executive Director

This year was a busy but successful one for Big Car. It started with our three-year pop-up socially engaged arts experiment, Service Center for Culture and Community, closing after a market-rate tenant leased the space. In the middle of relocating and expanding our work to include Downtown Indianapolis, we accomplished much, including:

• Three major public events attracting 5,000 people (the TEDxIndianapolis conference at Hilbert Circle Theatre, the Art in Odd Places public art experience Downtown, and No Brakes 10-year Big Car retrospective at University of Indianapolis).

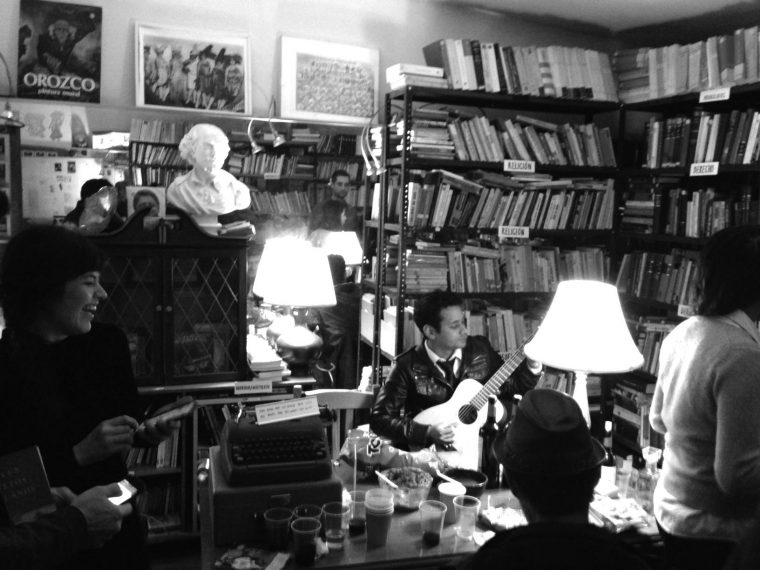

• Pop-up cultural spaces on three sides of town lacking easy and free access to cultural opportunities (Lafayette Square, Far Eastside, Near Southside) including a new sound-art gallery curated and organized by one of our artist fellows, John McCormick, a recent Herron School of Art MFA graduate.

• Three major murals in Central Indiana and nine more nationwide — all created in collaboration with community members, involving more than 2,500 people in making art, and helping beautify a variety of public spaces.

• Design work for 15 fellow nonprofits, including a virtual historic tour of the Athenaeum — and logos and other materials for Ensemble Music Society, iMOCA, White River Festival, Garfield Park Neighbors Association, Reconnecting to Our Waterways, and Youth Power Indiana.

As part of a NUVO Newsweekly cover story in September highlighting Big Car’s 10 years of working Indianapolis, writer David Hoppe called Big Car artists “impresarios of the imagination,” using our creative expertise to “benefit people where they live.” This, as always, continues to be our goal. Read the rest of Hoppe’s story here.

In 2015, the theme of the annual TEDxIndianapolis big ideas conference we lead will be “Keep it Simple.” We plan to use this as a guiding principle for our approach for 2015. One way we plan to simplify is to focus more of our programming this year on a particular neighborhood — Garfield Park just south of Fountain Square. Look for exciting details soon on a new home base we’re establishing there. A good portion of our work in the early part of 2015 will be focused on launching this location while also advocating for neighborhood-wide improvements and furthering our relationships with community partners there.

We’ll continue pop-up programming and projects in Lafayette Square and the Far Eastside, including the summer-long partnership with the Indianapolis Public Library that pairs our mobile art-experience unit — the DoSeum — with the Bookmobile, making stops at apartment complexes in very challenged areas of the city. There, Big Car artists make art with young people and share free, healthy snacks. We call this entourage Fun Fleet and we look forward to another summer of fun in these neighborhoods.

And we’ll again bring a few major citywide projects to Indianapolis in 2015. The biggest is a partnership with the City of Indianapolis to bring arts programming to Monument Circle from June to September. Funded by a National Endowment for the Arts Our Town awarded to the City and Big Car, this work — also in partnership with Art Strategies — will include temporary, site-specific cultural programming that helps the community reimagine what can happen at the Circle.

We’ll also further expand our work to make public sculptures using salvaged honeysuckle wood removed from waterway areas around the city. We’ve created a system for volunteers to clear the invasive honeysuckle, which blocks views of our waterways and kills native species, and then repurpose it as building material for chairs, benches, arbors, and other sculptures. Our artists work with volunteers, including young people from the TeenWorks program, to design and collaboratively build the pieces, which are often placed in public areas near the waterways.

Our audience in 2015 will continue to be a blend of primarily lower-income residents who don’t have easy access to art, and an arts audience (including many local artists) that continues to support Big Car and our work. We believe connecting people who are newer to the arts with existing arts supporters and artists is crucial to expanding the arts audience in Indianapolis. And we believe involving people in making art helps them better connect with it and appreciate it.

All of the artists at Big Car see working with people to improve the quality of life as our artistic practice. It’s not a side outreach program. It’s not something we do for a living, begrudging, while we wish we were doing our art. While many of us still make other kinds of art, our work with people is integrated with this practice. And our personal passions — the issues that mean the most to us — are integrated into our approach to the work we choose as an organization.

What we strive to create at Big Car is a better world, starting with our own community and our own neighborhoods. We use the tools and the power of art to help people become more culturally and creatively inclined, happier, healthier, more active and engaged, and better connected to each other in an increasingly divided world. That’s our art, as it should be. And, ultimately, it’s everybody’s art.